If you are familiar with the literature or the word " Terrorism", then you realize that this is a fool’s errand.There is little consensus among the Inteligencia or academics on who practices terrorism and what constitutes terrorism; let alone the military, intelligence agencies, the judicial system, and government who formulate the definition and meaning to their own need and requirement

Now the word terrorism was formulated and born during French Revolution of 1789 as the label used by the establishment to describe the conduct of revolutionaries and vice-versa.

|

| "Inside a Revolutionary Committee during the Reign of Terror" |

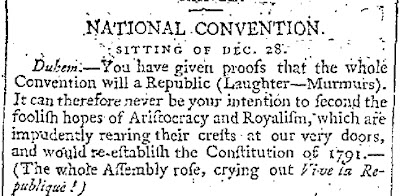

When did the word terrorism find its way into the English language?

This excerpt from January 30, 1795, edition of the London Times, reporting on the French National Convention in Paris, appears to be the First Mention of the word in English.

The article begins like this:

NATIONAL CONVENTION SITTING OF DEC. 28 Duhem:–You have given proofs that the whole Convention will a Republic (Laughter–Murmurs). It can therefore never be your intention to second the foolish hopes of Aristocracy and Royalism, which are impudently rearing their crests at our very doors, and would re-establish the Constitution of 1791.–(The whole Assembly rose, crying out Viva la Republique!) |

Later in the transcript, Monsieur Brsard utters the word that suddenly was part of the English language, and which occupies more news today.

Brzard.–“There exists more than one system to overthrow our liberty. Fanaticism has raised every passion; Royalism has not yet given up its hopes, and Terrorism feels bolder than ever.”

The difficulty in defining “terrorism” is in agreeing on a basis for determining when the use of violence (directed at whom, by whom, for what ends) is legitimate; therefore, the modern definition of terrorism is inherently controversial.

UN General Assembly Resolution 49/60 (adopted on December 9, 1994), titled "Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism," contains a provision describing terrorism:

Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any other nature that may be invoked to justify them;

Definitions of terrorism in other UN decisions

In parallel with the criminal law codification efforts, some United Nations organs have put forward some broad political definitions of terrorism.

UN General Assembly Resolutions

A 1996 non-binding United Nations Declaration to Supplement the 1994 Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism, was included in UN General Assembly Resolution 51/210, which described terrorist activities in the following terms:

- Strongly condemns all acts, methods, and practices of terrorism as criminal and unjustifiable, wherever and by whomsoever committed;

- Reiterates that criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or other nature that may be invoked to justify them;

UN Security Council

As per the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1566 (2004) condemned terrorist acts as: Recalls that criminal acts, including against civilians, committed with the intent to cause death or serious bodily injury, or taking of hostages, with the purpose to provoke a state of terror in the general public or in a group of persons or particular persons, intimidate a population or compel a government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act, which constitute offences within the scope of and as defined in the international conventions and protocols relating to terrorism, are under no circumstances justifiable by considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or other similar nature, and calls upon all States to prevent such acts and, if not prevented, to ensure that such acts are punished by penalties consistent with their grave nature;

High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges, and Change

The United Nations' High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges, and Change was created in 2003 to analyze threats and challenges to international peace and security and to recommend action based on this analysis.It was chaired by former Prime Minister of Thailand Anand Panyarachun

The panel focused on state terrorism and asked its member states to set aside their differences and to adopt, in the text of a proposed Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism, the following political "description of terrorism":

“That definition of terrorism should include the following elements:

(b) restatement that acts under the 12 preceding anti-terrorism conventions are terrorism, and a declaration that they are a crime under international law; and restatement that terrorism in a time of armed conflict is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions and Protocols;

(c) reference to the definitions contained in the 1999 International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism and Security Council resolution 1566 (2004);

(d) description of terrorism as “any action, in addition to actions already specified by the existing conventions on aspects of terrorism, the Geneva Conventions and Security Council resolution 1566 (2004), that is intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants, when the purpose of such act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a Government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act”.

(d) description of terrorism as “any action, in addition to actions already specified by the existing conventions on aspects of terrorism, the Geneva Conventions and Security Council resolution 1566 (2004), that is intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants, when the purpose of such act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a Government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act”.

Proposed Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism

Since 2000, the United Nations General Assembly has been negotiating a Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism. The definition of the crime of terrorism, which has been on the negotiating table since 2002, reads as follows:

1. Any person commits an offence within the meaning of this Convention if that person, by any means, unlawfully and intentionally, causes:

(a) Death or serious bodily injury to any person; or

(b) Serious damage to public or private property, including a place of public use, a State or government facility, a public transportation system, an infrastructure facility or the environment; or

(c) Damage to property, places, facilities, or systems referred to in paragraph

1 (b) of this article, resulting in or likely to result in a major economic loss, when the purpose of the conduct, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population or to compel a Government or an international organization to do or abstain from doing any act.

2. Any person also commits an offense if that person makes a credible and serious threat to commit an offense as set forth in paragraph 1 of this article.

3. Any person also commits an offence if that person attempts to commit an offense as set forth in paragraph 1 of this article.

4. Any person also commits an offense if that person:

(a) Participates as an accomplice in an offense as set forth in paragraph 1, 2 or 3 of this article;

(b) Organizes or directs others to commit an offense as set forth in paragraph 1, 2 or 3 of this article; or

(c) Contributes to the commission of one or more offenses as set forth in paragraph 1, 2 or 3 of this article by a group of persons acting with a common purpose. Such contribution shall be intentional and shall either:

(i) Be made with the aim of furthering the criminal activity or criminal purpose of the group, where such activity or purpose involves the commission of an offense as set forth in paragraph 1 of this article; or

(ii) Be made in the knowledge of the intention of the group to commit an offense as set forth in paragraph 1 of this article.

.jpg)