Introduction

Professor Nigel Walker (1980) Director of the UK Institute of Criminology, argued that ‘limiting principles’ exist indicating when the criminal law should or should not be used, eg.- It is better to prevent than punish

- The law should not be used to penalize behavior that does no harm;

- The law should not be used to compel people to act in their own best interests.; etc.

Defining Deterrence

Deterrence involves the threat of punishment via some form of sanction.Deterrence is a way of achieving control through fear.If motorists do not refrain from offending out of fear of consequences they are, by definition, not deterred.

Deterrence, in general, is the control of behavior that is affected because the potential offender does not consider the behavior worth risking for fear of its consequences.

Beyleveld (1979) defines the essence of deterrence by two criteria:

A “deterrent effect” of sanctions is the preventive effect of the sanction(s) resulting from the fear that the sanction(s) will be implemented.

Thus “deterrence” refers to any process by which the threatened act is not committed (or is at least hindered) because of the deterrent sanction. Strictly defined (Beyleveld 1979,p.207)

“A person is deterred from offending by a sanction if, and only if, he refrains from that act because he fears the implementation of the sanctions, and, for no other reason.”

Deterrence is therefore but one compliance-gaining mechanism.

Beyleveld (1979) defines the essence of deterrence by two criteria:

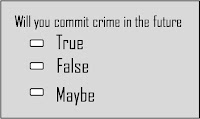

Given X’s negative attitude towards the imagined experience of undergoing what he believed were the actual penalties he risked if he committed C1., his positive motivation to commit C1, and the chance he believed existed of having what he believed were the risked penalties being inflicted upon him if he committed (or attempted to commit) C1, and the chance he believed existed of successfully fulfilling his motivation to commit.C1, X “decided” that the personal utility of not committing C1 exceeded the personal utility of committing (or attempting to commit C1 . (16) This ‘calculation’ of utility was the reason why X did not commit C1. (Whatever other factors may have weighed towards X not committing C1,this calculation was necessary for X not to have committed C1, and the calculation alone or in conjunction with other factors was sufficient for X not to have committed C1).” (p.209)

Thus “deterrence” refers to any process by which the threatened act is not committed (or is at least hindered) because of the deterrent sanction. Strictly defined (Beyleveld 1979,p.207)

Deterrence is therefore but one compliance-gaining mechanism.

How Does the Deterrence Operate?

The mere presence or introduction of a sanction may hinder or prevent an offense in a number in different ways:- Knowledge of the sanction affects the perception of the cost of offending so that compliance is seen as more attractive than offending;

- Knowledge of the sanction, coupled with a belief in the sanctity of law or unquestioning legal authority, may be sufficient for compliance;

- Sanctions may also have moral-educative and habituative effects so that they may be causally involved in the generation of moral beliefs and inhibitions, and laws may be obeyed purely by force of habit;

- The implementation of sanctions, rather than the mere threat may reduce offenses by incapacitating potential offenders, reforming them or by creating via stigmatization of the offender, informal pressures to comply.

The philosophy underpinning deterrence is that the risk to the lawbreaker must be made so great and the punishment so severe, that people believe they have more to lose than to gain from the offense.

Deterrence in the literature, and in practice, is usually only in reference to a legal sanction but non-legal sanctions such as fear of ostracism or the disapproval of others are also capable of acting as deterrents.

.jpg)